The Continuing Hurt: An issues and discussion paper to provoke reflection.

Prepared for members of The Awareness Party by Dr Benjamin Pittman.

In relation to two key critical founding events in New Zealand, He Wakaputanga (1835) and Te Tiriti o Waitangi (1840), it is obviously difficult for most non-Māori today, ignorant of and disinterested in the true facts of our history to understand the immense breach of honour, trust and faith which has occurred, virtually unbroken, and how both actions and inaction have served effectively and progressively to trample the mana[1] inherent in individual and collective rangatiratanga.[2] Our rangatira[3] were not stupid; they were trusting and used to dealing with all things with attendant mana and honour. To them, Te Tiriti o Waitangi was a kawenata,[4] a covenant. To it they attached their mana and rangatiratanga absolute.

Ngā tuhituhinga tuatahi o te Tiriti o Waitangi ko ngā moko o ngā rangatira o Ngāpuhi.

The first signatures on Te Tiriti o Waitangi are the tattoos of the chiefs of Ngāpuhi.

They also knew of the deceit, lies and thievery to come and of the allied diseases and lifestyle changes forced upon them and trampled into their being. Choice and new options were often to take on an ugly face. For them, the pākehā[1] collectively, was to prove a pestilence personified. Our rangatira knew already when pākehā arrived that they were coming in numbers: tohunga matakite[2] had foretold of the event long before and so, on 27 November, 1769, when Captain James Cook, RN, and HMS Endeavour rounded Motukokako, my great-great-great grandfather, Tapua as tohunga,[3] war leader and rangatira, was waiting with 220 men in four waka,[4] Te Tumuaki, Te Harotu, Te Homai and Te Tikitiki. But, they were also practical people and while they waited, they fished. This was to be the start of a troubled relationship; a troubled history and when we look back, for Māori, one of unimaginable and tragic loss.

Fast-forward to November 1830. Patuone, son of Tapua and my great-great grandfather,

was in Sydney on a trading mission on aboard the Sir George Murray. This was the first ship European-style ship built in New Zealand, at Horeke in the Hokianga, and part-owned by Patuone and his close relative Taonui, both of whom provided the timber. The Sir George Murray had been built in partnership with the Sydney merchants, Gordon Brown and Thomas Raine. Upon arrival in Sydney on 18 November, 1830, the maiden voyage, the ship and cargo were impounded by customs officials, due to a breach of the British navigation laws operating in New South Wales at the time. These laws required all ships engaged in trade to have a flag of nationality and a register, detailing construction and ownership. The ship and Patuone, who was accompanied by two sons and his relative, Taonui, had sailed into an unpredicted dilemma and controversy: Māori[1] New Zealand was neither British, nor did it have a flag to comply with official requirements. It was the first foreign encounter Patuone was to have with what was later to become the vexed issue of rangatiratanga. He and others knew and asserted their rangatiratanga at home but, now the rules were different: this was a situation involving rangatiratanga in another context; a foreign context which required the symbols of rangatiratanga; in this case, a flag and a ship’s register. Realising the delicacy of the entire situation with two powerful and senior Ngapuhi rangatira aboard and also, remembering the Boyd massacre at Whangaroa in 1809, the authorities in Sydney were forced to handle the matter very carefully and delicately, drawing on lessons previously learned.

Then, in November, 1831, thirteen of our rangatira gathered together at Waimate: Patuone, Nene, Te Wharerahi, Taonui, Rewa, Kekeua, Titore, Te Morenga, Ripe, Hara, Atuahaere, Moetara and Matangi. Alarmed at pākehā lawlessness, they wanted King William IV to know of their concerns. They wrote a letter dated 16 November 1831. They already knew about the arrogance of empire with the various powers of the day seeing it all as part of the normal process of events as ‘superiors’ above all to divide up and exploit the parts of the planet deemed unclaimed and uncivilised. Unclaimed and uncivilised often came to mean, uninhabited, an arrogant discounting of the millions who in fact lived there.

On behalf of King William, Lord Viscount Goderich, a principal Secretary of State addressed to the ‘Chiefs of New Zealand’ a letter of assurance in reply dated 14 June 1832. In it he referred to the ‘close commercial intercourse’ between the inhabitants of New Zealand and those of Great Britain. He spoke of ‘mutual goodwill and confidence’ and of ‘friendship and alliance with Great Britain’. It was an auspicious start of great comfort to our rangatira. This was followed on 24 March, 1834 by our true founding symbol as a nation, our first national flag, and then on 28 October, 1835, He Wakaputanga, which declared the independence of the United Tribes of New Zealand and the founding of their nation. While He Wakaputanga was essentially a Ngapuhi matter to begin with, the longer-term intentions of the founding rangatira were to include other iwi[1] groupings as well, this capacity to become allied in the development of a wider, pan-Maori rangatiratanga being expressed in the document’s declaratory sections. Both Te Hapuku (Ngati Kahungunu) and Potatau Te Wherowhero (Waikato-Tainui) signed on to start the process, beyond Ngapuhi. While other iwi groups, including Tuhoe, would have heard about this proposition of the assertion of a collective rangatiratanga, the course of events stalled with offshore opposition from pākehā instrumentalities apparently exerting undue influence, which should never have occurred. Tuhoe of course, inter alia, refused to sign the later Te Tiriti o Waitangi. So, He Wakaputanga was a declaration of independence by rangatira of their rangatiratanga in a collective and national sense. In a pākehā sense, all denials aside and irrelevant, sovereignty had been declared.

For me, for us as Ngapuhi, all of this is not merely historical detail and fact; it is part of a history lived and carried on; a history brought forward so that it is never forgotten or overlooked because it all remains part of the intrinsic and complex solution we all seek to the contemporary predicament of Māori. In a sense, therefore, I carry within me an unfulfilled mission; one laid down by my great-great grandfather, Patuone, by my great-great grand uncle, Nene (Tamati Waka Nene) and by our other great rangatira. It is significant that I am far from alone. And of course, this is not just about me; it includes all our other whanaunga[1] who are integrally part of an on-going struggle for true justice. And of course, this is repeated over every family group, every hapu and every iwi as well as extending to pākehā of awareness and goodwill. In 2015, it is 179 years since He Wakaputanga and 175 years since Te Tiriti o Waitangi. While in the scheme of things, these are comparatively short periods upon the often troubled map of history, this gives no comfort to Māori: there is much unfinished business, betrayal, a trampling upon mana and the perpetration of a massive and continuing fraud and denial. While the hurt is palpable and undeniable, we must all accept one key fact: true justice has no use-by date.

Now, there always has been a certain romance about pākehā settlement of Aotearoa; the brave and intrepid coming to a wild, harsh and untamed land, awaiting exploitation and, its natives, the supreme and wonderful gift of European civilisation. Much has also been made about the capacity and adaptability of Māori as one of the highest examples of Rousseau’s Noble Savage. However, from the beginning, the political analysts—amateur and professional—realised one critical point: the true vulnerability of Māori was their concept of rangatiratanga. Although rangatiratanga would eventually be declared in a collective sense with He Wakaputanga in 1835, since each rangatira held and exercised his or her own rangatiratanga as well, it came to be seen as a means to divide. In turn, apart from the facts and process of history as it unfolded, the polarisation of Māori created its own mythology and sense of heroics.

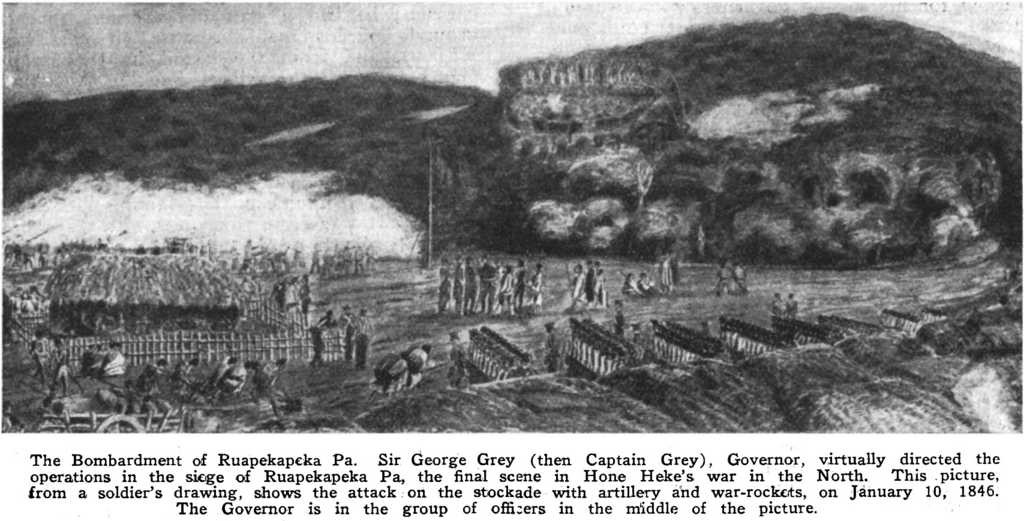

Nowhere is this more marked than in Ngapuhi and, the culmination of all was Ruapekapeka. The true and full story is far more interesting and complex than is generally read, believed or even told.

And yet, the great trampling of these things has a price and, as a child, for my kaumātua,[1] events such as the 1953 Tangiwai train disaster and the 1963 Brynderwyn bush crash which occurred during visits by the current British Queen, indicated how the British Government along with the many iterations of New Zealand Government, have unfinished business, injustice and unresolved issues which still need to be confronted and resolved properly and fully in a spirit of true justice. Other national disasters are also considered part of a kind of national utu[2] of the unresolved: the Napier Earthquake of 1931; the Wahine disaster of 1968 and the more recent earthquakes in Christchurch. Such tragedies are a reminder of lingering injustice and also a warning. For Māori and others who remember and reflect, justice has no use by date and all will continue until a proper acknowledgment is made and recognition given to all our tupuna[3] agreed. Not to do this with honesty, integrity, goodwill and honour is to risk the wrath of our tupuna going forward. They sit there watching and waiting as guardians and sentinels. While settlements of grievances under breaches of Te Tiriti o Waitangi have occurred, the processes have been long and arduous and nothing can ever atone for the inestimable losses and assaults upon Māori rangatiratanga and mana whenua,[4] along with all they include and engender. Rebalance under the laws of utu—reciprocity, balance and re-balance—remains a work-in-progress with, however, negotiations taking place within a system and structure which is totally skewed. We see it quite simply as the thief setting the rules of engagement for his prosecution with the facts and reality of history, truth and justice all set aside as expedient. This is especially so for Ngapuhi, the last and the major settlement process on the table. For those truly interested in truth and fact, essential reading should be ‘Ngapuhi Speaks’ (2012) and ‘He Whakaputanga me Te Tiriti – The Declaration and the Treaty’ (2014) the former the collective Ngapuhi world view and the latter the Waitangi Tribunal report of Stage I of the Paparahi o Te Raki[5] Inquiry. But, who in Aotearoa today, other than us and a few others really care?

Further, atonement and dissipation of collective guilt through long-awaited

apologies and good works through settlements under Te Tiriti o Waitangi are truly nothing to be proud of. As well as being a mere drop in the ocean for all that has been lost, stolen, misappropriated and trampled upon, total settlements to date are around the $2billion mark. The insignificance of this total gets thrown into its true perspective when we consider the annual acts of government largesse, its corporate welfare program amounting to many billions every year and one-off rescues such as the Canterbury Finance bailout alone amounting to $1.77billion. Add to this Canterbury water, and the list goes on. The obscenity of this is appalling: patronising crumbs for the disinherited and denied; a gold pass for their mates.

Along the complex pathways of co-existence, Māori have been progressively and systematically victimised by ignorance, arrogance and process. On top of Māori suffering is the added insult of those with racist agendas and attitudes, multiplied by the collective arrogance and ignorance of numbers and with no awareness of or interest in the true history of our nation which was conceived by Māori as a true partnership with pākehā looking after their own and Māori autonomy guaranteed.

Of course, there are many pākehā of true good will and understanding whose sense of justice unfulfilled is every bit as powerful as ours. But, a handful of people have little influence once collective denial and amnesia take over. Government has to step up and do the honorable thing for once and restoration must be on-going.

The current system depends overall on numbers; all is a numbers game and a consolidation of power. People become victims of their own despair and withdraw, defeated without ever having been defeated and without any thought of exercising their personal and individual rights to have a say and participate in what is supposed to be a vibrant democracy. This is why their collective apathy, despair and loss of any hope helped in 2015 to re-elect a Key government, giving it a sense of self-righteousness for its anti-everything policies unless they are policies to support, promote and look after corporate mates and supporters. Not only do their eyes look beyond Aotearoa to a local post-plundering future; they look to the wider world of government and corporate mates to share the plunder here, while it is still available. Their true payoff will come of course in their life post-politics.

Fairness and a fair go no longer exist in an increasingly polarised Aotearoa

where the poor are demonised, blamed and penalised for their own predicament. We might all lament the choices and actions of those in political power, devoid of honour, scruples or conscience. Within this challenging mix, we have the romance of the Prime Minister’s humble, State house origins which perpetuates the myth that all is possible for those determined and with the necessary fortitude and grit upon the ever-upward trajectory towards self-betterment and ‘success’. But, of course the rules, realities, circumstances and opportunities are ever-changing so that the world of the 1940s, 1950s and 1960s when many of us were growing up, is not at all the same place with the same opportunities. Attitudes have become more self-centred and this is the current norm. The support and assistance Key and others received is no longer there: they have taken it away and worse still, now they want to auction off social contracts with a profit motive for though who buy in.

The support and assistance Key and others received is no longer there: they have taken it away and worse still, now they want to auction off social contracts with a profit motive for though who buy in.

The reality is that for most Māori in Aotearoa today, aspirations are still possible, however, unless they take as an example, the greed, self-interest, self-seeking of the system, they remain just that; aspirations and, many are simply trying to survive: one cannot eat or be housed by aspirations.

Historically, there are political parties with a proud history of standing up for the underdog and for a fairer Aotearoa. Even with the occasional self-immolation and choking event within this history, the record still stands. History contains many salutary lessons for those willing to forget, to repeat and to fall again. It is, however, time for a political party and an allied social movement to be the truly visionary and forward thinking party it should and must be: the ever vigilant and active conscience of the nation; the upholder of morality and justice for all and the agent to at last complete all of the unfinished and painful business remaining.

But, all of this is by way of key background. Aotearoa/New Zealand is fighting another battle and, this is a battle for survival as a democracy; for survival as an independent nation; for survival as a nation still coming to terms with the realities, lies, broken promises, racism and injustices upon which it was founded. In Ngapuhi, we have never given up our rangatiratanga, our sovereignty, to the British Queen or anybody else. But, today, under the Key government and its machinations, the threat to the greater rangatiratanga of all of us, Māori and pākehā, is very real. The reality behind the smiling false face of prosperity and promise is called the Trans Pacific Partnership Agreement (TPPA). It is the all-inclusive mechanism for selling us all down the drain and creating a future for none, other than its architects and promoters and those waiting for their payoff. It is self-centred exploitation gone mad.

The TPPA is a catch-all for disaster and a future even more exploitative, poisoned and toxic. Combine it with the Key government’s ambitions to minimise, simplify and emasculate controls in critical areas such as the Resource Management Act, while the moral authority and paramount status of Te Tiriti o Waitangi alone stands firm, the TPPA and the Key government will hand both our Māori rangatiratanga and our collective Aotearoa/New Zealand rangatiratanga to foreign and local corporate entities with no interest in anything but unbridled exploitation and profit for themselves. The fact that these taonga are not theirs to negotiate in secret and then to give away in the first place is one point; any attempt to do so is national betrayal and treason.

Kei a ratou nga he; kei a tatou te utu!

To them the errors and sins; to us all the re-balancing and taking back!

References / Translations

[1] Mana = personal status, standing, prestige, authority

[2] Rangatiratanga = sovereignty, based on absolute chiefly authority but exercised for the good of all

[3] Rangatira = hereditary chief

[4] Kawenata = covenant

[5] Pākehā = non-Māori person. Contrary to some assertions there is no insulting connotation here at all

[6] Tohunga matakite = a priest with the capacity to see into the future

[7] Tohunga = a priestly expert; practitioner of one or more of the priestly arts. Māori had highly sophisticated ‘levels’ and ‘baskets’ of knowledge: the practice of tohunga covered many different areas although some specialised in specific areas such as the tohunga ta moko who specialised in tattoos and the tohunga ta whakairo who specialised in carving. The ‘levels’ were ‘te mātauranga o te kauae raro’ – the knowledge of the lower jaw and ‘te mātauranga o te kauae runga’ – the knowledge of the upper jaw. The higher-level priestly arts sat in this upper level.

[8] Waka = canoe: there were many types and sizes culminating the large ‘waka taua’ – war canoes capable of seating up to 80.

[9] Māori = a term which came to be applied to the indigenous inhabitants of Aotearoa. Initially, Māori were called New Zealanders. As a term, Māori actually means common, natural, everyday, plain, as in ‘wai Māori’ = fresh water. It could also be applied to express the concept of ‘native people’. In traditional Māori society, one’s source and assertion of identity was firmly rooted in one’s whanau (family), hapu (sub-tribal nation) and iwi (tribal nation). This explains the great diversity and complexity of identity in today’s Māori world.

[10] Iwi = tribal nation

[11] Whanaunga = relatives

[12] Kaumatua = respected elders, male and female collectively. Kuia refers to female elders.

[13] Utu = often mistranslated as revenge when it is more about reciprocity, balancing and rebalancing, restoring and payment or returning/giving something of equal or greater value

[14] Tupuna = esteemed ancestors, also tipuna in some dialects

[15] Mana whenua = ancestral rights of control and links pertaining to land, areas and regions. Even where lands have been sold, overall mana whenua still applies.

[16] Paparahi o Te Raki = the claims inquiry process within the Waitangi Tribunal related to claims made under breaches of Te Tiriti o Waitangi.

Dr Benjamin Pittman, PhD(UTS), MFA(Hons) Auck., MHPEd(UNSW), BFA(Auck), DipTchg(NZ), DipSecTchg(ASTC), DipAPC(CISyd), Justice of the Peace for NSW #129064